You’ve Never Seen the Rio Grande Valley This Way

The Rio Grande Valley is not one of the easier places in America to build a career as a contemporary artist. The strip of predominantly blue-collar border towns and cities from the Gulf Coast and Brownsville up the river to Edinburg, McAllen, and beyond boasts few top-notch art institutions or deep-pocketed collectors. The scene can leave something to be desired too. On the porch outside Presa House Gallery in San Antonio, painter Donald Jerry Lyles Jr. tells me about a short-lived “art walk” series in McAllen. Nearby bar owners raised a stink, Lyles says, because the participating galleries were giving away free wine and cheese. The monthly event was kiboshed. So much for local patrons of the arts.

This month, Presa House is presenting “South of the Checkpoint/North of the Border,” featuring works, mostly paintings, by Lyles and fellow homegrown RGV artists Gina Gwen Palacios and Rigoberto A. González, all three of whom teach at the University of Texas–Rio Grande Valley. Bigger-city venues don’t often showcase RGV artists, and, as the exhibit at the DIY artist-run Presa House shows, that’s a shame. González, Lyles, and Palacios have unearthed rich veins of subject matter in the landscapes and people of the RGV, and their work deserves more reach. One gift that painters, especially, can give to the rest of us is the momentary ability to see a place more clearly, incisively, or transcendently than we ever could on our own. Each of the three artists on display, in his or her own way, offers that sort of singular, transformative interpretation of the Valley.

The most haunted vision probably belongs to Palacios, a Rhode Island School of Design graduate who hails from a family of migrant farmworkers based in and around the Valley. She speaks of

her art as uncovering and recovering in the landscape traces left by generations of agricultural workers, who made the Valley what it is today. Cotton is a go-to subject, as are endless fields, and the vanishing point of the road as it stretches to the horizon, giving the sense that one could drive forever (as farmworkers do over the course of their lives) without ever getting anywhere.

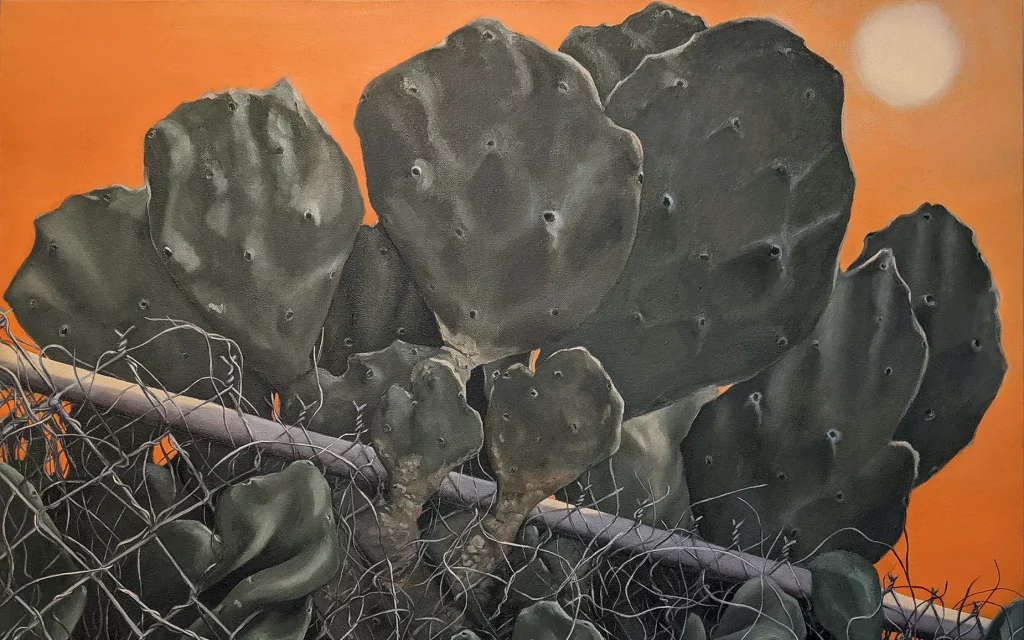

An especially precarious type of migrant experience—the dangerous overland trek from Mexico—is also suggested in several of Palacios’s canvases: blue barrels in a scrub desert, the word “AGUA” crudely painted on their sides; a patch of rough-hewn wooden crosses in an overgrown rural cemetery; the big prickly pear cactus that has forced itself through a chain-link fence. Everywhere in her paintings, systems of order are buckling under the forces of nature—lines of telephone poles sagging to one side, roads filling with puddles of rain. People are absent, except for one portrait of her farmworker aunt and young cousin standing in a ragged field. It’s titled American

Primitive, a reference to an album by folk-music compiler and guitarist John Fahey, but also to Grant Wood’s iconic painting American Gothic.

The latter allusion underlines some key questions posed by the entire “South of the Checkpoint/North of the Border” exhibition. The artists are following in the footsteps of American Regionalism, the pre–World War II art movement that rejected abstract

styles then arriving from Europe

and instead focused on realist depictions of the so-called heart

land. What happens when this approach is taken to the RGV, an island-like region seemingly off the edge of America, beyond the Border Patrol checkpoints? Is life in the RGV such a far-out situation, or is Valley reality just as central to American reality as is, say, an Iowa farm? And by looking deeper into RGV reality, might the rest of America begin to learn a few important things about itself (such as, for instance, who actually does the work of harvesting our crops)?

González stands out amid his colleagues as the most technically exacting image-maker. He says he works on paintings and drawings for as long as a year, fine-tuning details, and it shows. He’s the sort of classically oriented painter who invites you to lose yourself in a still life, in the swirling skin of a pomegranate or the shadowed hues of a flower. But his imagination, at least in his work on display here, is more politically inclined. His largest work features a young woman in a bruised protective stance in front of a length of border wall. The wall is solid enough to impede her (or to keep her safe from dangers on the other side), but nearby butterflies effortlessly flit through the space between the slats. González sees the work as a tribute to undocumented migrant women, who are especially vulnerable during their journey north.

The painting serves as a stark reminder of the traumas lurking beneath the surface of immigrant life, hidden histories of suffering that those of us born on the north side of the wall can easily ignore. González was born in Reynosa, on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande, and is interested to tell the stories of border-crossers in rich pictorial contexts that evoke pre-Modernist European and American art. That involves developing mythologies, such as in his series The Creatures of Prometheus, which includes large-scale pencil drawings of a coyote and a hawk. Both animals have double meanings. The hawk, Gonzalez says, represents the bird in Greek myth that pecks out Prometheus’s liver for eternity as punishment for his theft of fire from the gods, but also the aerial drones that patrol the skies above the borderland in pursuit of migrants. Meanwhile, the coyote, he explains, mirrors the role of Greek Prometheus in Indigenous American myths of divine fire theft. And “coyote,” of course, is also the term for those who transport migrants through Mexico and across the border, often treating them viciously along the way.

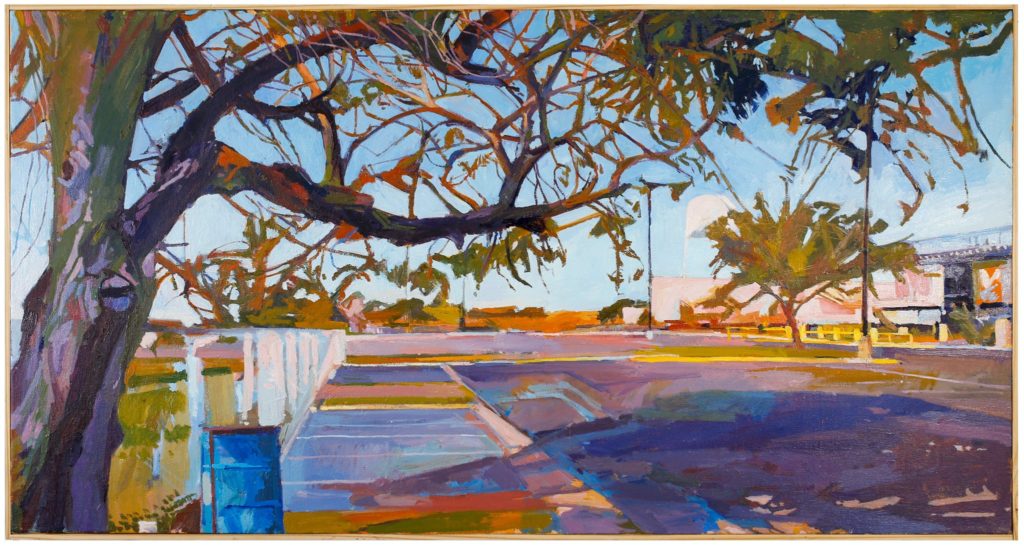

In comparison with the grand-scale, identity-oriented work of his colleagues, Lyles’s neighborhood landscape paintings can come across as humbler and more surface-level, but he’s up to something subtly incisive. His bone to pick, he explains, is with land-use policies and zoning as the RGV has developed in recent decades from an agricultural plain (as seen in Palacios’s work) to more of a homogenized concrete-and-pavement Anytown, USA. Born and raised in Edinburg, Lyles feels a kinship with the native plants and trees of the region, and he tends to paint them where he finds them, these days often encroached upon by aesthetically aggravating new arrivals like cookie-cutter tract homes, chain stores, and parking lots.

This jibes with my personal experience of the landscape of the RGV, which, at least prior to my time with “South of the Checkpoint/North of the Border,” mostly stuck in my mind as a flat monotony of low-density sprawl. It does strike me as odd, in retrospect, that a place like the Valley could be so unique in its isolation between border and checkpoint and yet also so drearily dull in what it is becoming on an aesthetic level. Lyles makes a case for the beauty that local nature has to offer, and he presents it in a palette particular to his eye, rich in purple shadows, light blue skies, and mossy greens.

Perhaps every American city has a few homegrown painting talents who can summon rich art from the familiar landscapes of their hometown. Apart from that, there’s nothing revolutionary to the eye in “South of the Checkpoint/North of the Border.” This exhibition is valuable as a window to a hard-to-pin-down, little-understood place. Here, the Valley

coheres in the imagination into a myth, an enchantment, a song. It’s up to those who know the place well to judge how true it rings and what’s missing, but, as an outsider, I was drawn closer.